↓

Scrolling Past

Pittsburgh, PA

inter·punct

Fall 2018

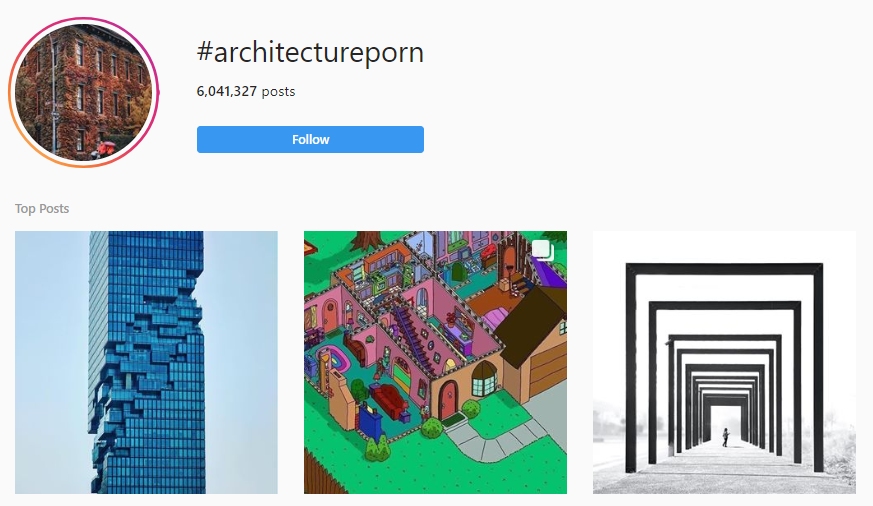

I’d like to invite all of you to check your Instagram before reading this. Maybe venture over to Pinterest or Behance if you’d like. While you’re at it, give Facebook and Twitter a good scroll through too. As a product of our generation, age, and graphic-based profession, our daily lives are saturated with media. 95 million photos and videos are shared on Instagram each day1. It is disrupting and agitating trends, diluting and dematerializing authority, and affecting the way we perceive spaces and images like no other platform.

The sheer amount of content thrown at us is a major catalyst of burnout syndrome, one of the plagues of our age2, as identified by architectural historian and writer Beatriz Colomina. Being constantly inundated with information, regardless of its quality, forces us to compare our own work to that of unknown authors potentially thousands of miles away. The nature of the images shared is also problematic, as we only see the best of the best and there is virtually no sharing of process work or the “second-best” render.

Moreover, this constant stream of graphical precedent has a clear effect on our design methodologies. As students, we can almost shop for a representational style, parti diagram, or formal language from the myriad examples we see every time we open our feeds. The build-up and availability of past knowledge is in general a clear marker of societal progression, but the trap is that it becomes much easier to regurgitate instead of reinvent.

inter·punct

Fall 2018

I’d like to invite all of you to check your Instagram before reading this. Maybe venture over to Pinterest or Behance if you’d like. While you’re at it, give Facebook and Twitter a good scroll through too. As a product of our generation, age, and graphic-based profession, our daily lives are saturated with media. 95 million photos and videos are shared on Instagram each day1. It is disrupting and agitating trends, diluting and dematerializing authority, and affecting the way we perceive spaces and images like no other platform.

The sheer amount of content thrown at us is a major catalyst of burnout syndrome, one of the plagues of our age2, as identified by architectural historian and writer Beatriz Colomina. Being constantly inundated with information, regardless of its quality, forces us to compare our own work to that of unknown authors potentially thousands of miles away. The nature of the images shared is also problematic, as we only see the best of the best and there is virtually no sharing of process work or the “second-best” render.

Moreover, this constant stream of graphical precedent has a clear effect on our design methodologies. As students, we can almost shop for a representational style, parti diagram, or formal language from the myriad examples we see every time we open our feeds. The build-up and availability of past knowledge is in general a clear marker of societal progression, but the trap is that it becomes much easier to regurgitate instead of reinvent.

Architecture has become pornographic. No foreplay, no experience, simply a feasting to the eye. As the Money-Shot comes to define the entire project and buildings can be sold using a single image, capitalist motivations discourage the architect from putting further thought into the project. We see this in school too: representation can obfuscate a lack of any theoretical, social, or even functional concept in a project, and — depending on who you ask – justifiably so. It is a line we all carefully walk.

The phenomenon of archi-porn is not new, the basic notion could perhaps be traced back to Venturi and Brown’s “ducks” vs “sheds” in Learning from Las Vegas. The contemporary definition of the two types may be unclear but creating “Instagrammable” architecture is widely prioritized above issues of traditional architectural discourse i.e. private/public, form, space, and order. The square-cropped interface of Instagram has become the new lens through which we perceive space. Flat and filtered, the image becomes more desirable than the architecture.

Text has taken a backseat in discourse. Images scroll by, while text is limited to [functionally] 280 characters. The role of the authoritative, influential critic is practically dead. The most popular architecture websites like Dezeen and ArchDaily present content with no analysis, thought, or editorial comment. Architectural profiles on Instagram herald every post as “fantastic work”, offering little insight into what makes it fantastic. The discourse has moved out of the institution into the comments section — the new platform for architectural criticism.

The idea that a single critic can define nearly an entire architectural movement — like Banham with Brutalism or Jencks with Postmodernism, feels outdated and quite frankly impossible in the contemporary situation. The proliferation of image and opinion has led to an increased difficulty in establishing a critical body of thought around any particular position. Are we experiencing the end of -isms? It may be the case that we are never able to gather enough momentum to establish an overarching architectural style to categorize our moment. The internet has allowed any and everybody to validate their opinions — no matter how preposterous — with countless like-minded people. Good criticism is still being written, but it is increasingly washed over by the rising tides of sheer data. The dialectic of Fact vs Fiction has dissolved into a sea of mere information.

Simon Nora and Alain Minc warned us about this exact situation in 1976. The pair was asked to issue a report on the dangers and possibilities of a computerized society to advise the current president of France. They predicted a situation in which everyone connected to the network could manufacture and disseminate information, leading to an incoherent and disjointed culture and a loss of trust in the truthfulness of content3.

This is not necessarily new either. When we think back to faux communist governments, we see a similar use of blanket equality to cover discriminatory practices. What is different and unsettling about our contemporary situation is the uncertainty of who is directing our information. Every platform we use to view information filters the data in its own way, with some of the more visible culprits taking the form of suggested friends and personalized ads.

Opinions diverge in face of our current moment. David Ruy writes, “I am puzzled and dismayed by how the left end of the political spectrum seems to be abandoning architectural speculation…How can the world be more progressive if everything remains the same or goes backward towards the historically familiar?”[4], while Ryan Scavnicky (@sssscavvvv) writes, “Critics must develop fresh audiences by using strange and experimental critical forms and reflecting those findings back onto the architecture discipline.”[5] — citing memes as the new modality of architectural provocation.

From another angle, the criticism of the public can often be more beneficial for the design process than that of a critic. Architecture is inherently tied to the public realm, and these same networks can be used to increase the transparency of design decisions that will inevitably affect them. In areas of social interest design and community-based projects, integration of social media into the design process could become a particularly vital methodology.

Crowd-sourced design doesn’t sound particularly appealing, but at the end of the day, anything is possible if you smash that like button.

Read the full issue at www.interpunct.pub